How Memory Works and Why We Forget: An Herbalist’s Guide

discover how the brain builds, stores, and sometimes loses memory — and how herbal wisdom offers gentle support along the way.

Memory isn’t just a vault where our lives are stored.

Truthfully, we don't even think about it until it starts to slip.

We remember our childhood friends, our first crush, that English teacher in high school who seemed far meaner than necessary, or even an awkward, embarrassing moment from ten years ago that nobody but you remembers. (really, stop stressing, I promise, no one remembers that anymore).

But at some point, we start noticing the small slips.

Why did I walk into this room?

Shoot, I met her last week — what was her name again?

Where the heck are my keys?

Maybe we notice it happening to ourselves.

Maybe we notice it happening to our parents, or the people we love.

We often think of memory as something we either have or we lose, but the truth is more alive than that. Memory is a dynamic process, constantly being shaped by what we pay attention to, what we feel, and how we experience the world around us.

Every moment becomes a quiet negotiation between what the mind will hold onto and what it will let drift away.

In a world that demands we move faster, remember more, and juggle endless streams of information, it’s worth pausing to ask:

How does memory actually work?

Why do some moments stay with us forever while others vanish almost immediately?

And what can we do — if anything — to protect this essential part of who we are?

Today, we’ll explore the architecture of memory: how fleeting experiences become lasting imprints, how the brain stores and preserves our moments, and where ancient allies like Ginkgo biloba might quietly support that process.

Because memory isn’t just something we have.

It’s something we are.

Memory: The Architecture of How We Remember

Most of us think of memory as a part of the brain that simply stores what we live through, like putting old photos into boxes. But memory isn’t nearly that still.

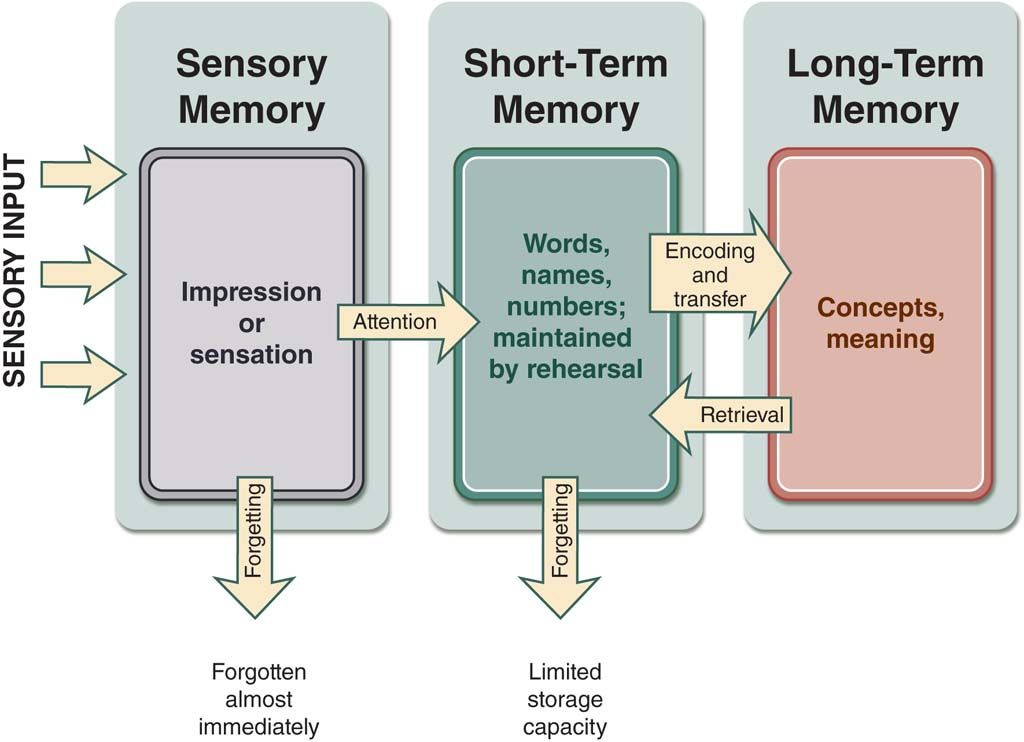

Memory is a dynamic process: a constant interplay between taking in information (encoding), holding onto it (storage), and calling it back when needed (retrieval). From the moment we experience something, a decision is being made, often unconsciously, about whether it will become a lasting part of us or simply fade into the background.

Most of what we perceive each day - a flash of color, a brief sound, the brush of the wind - disappears almost immediately. It lingers for just a fraction of a second in sensory memory, the brain’s first and most fleeting form of holding information.

Sensory memory is modality-specific. Visual impressions leave a quick afterimage called iconic memory, and sounds leave a brief trace called echoic memory. These tiny snapshots give us a chance to focus, and if we do, the information moves on to the next stage.

That next stage is short-term memory, sometimes called primary or active memory.

Short-term memory acts like a mental workbench, temporarily holding a small number of pieces, typically around seven items, give or take a few. Without conscious rehearsal, this information only lasts about 15 to 30 seconds before it fades.

Short-term memory is what lets you remember a new name long enough to say it again or hold a list in your mind as you move through a store. It pulls from the sensory impressions that caught your attention, giving you just enough time to decide what’s worth keeping.

Closely tied to this system is working memory: the process that doesn’t just hold information but actively works with it.

Working memory is what lets you do mental math, organize your next sentence, or picture how to rearrange furniture in a room.

It’s your brain’s temporary sketchpad, constantly shifting and updating based on what you’re doing.

Where short-term memory is like keeping a few books open on a table, working memory is like flipping through those books, taking notes, and rearranging ideas.

Without working memory, problem-solving, learning, and even holding a basic conversation would be almost impossible.

Of course, not everything that enters short-term or working memory is destined to last.

Only a fraction of experiences and pieces of information are deemed important enough to begin the journey into long-term memory, where they can settle into the architecture of the mind for months, years, or even a lifetime.

From Fleeting Moments to Lasting Imprints: How Memories Are Stored

Not everything our brain touches stays with us.

In fact, most of what we see, hear, and feel each day fades out before we’re even aware it existed. And that's actually a good thing. If we remembered everything, our minds would be so cluttered we’d hardly be able to think at all. (…even though this is how my mind feels on a day to day basis)

The brain is selective for a reason.

It filters, organizes, and decides what’s worth keeping based on how much attention we give it, how meaningful it feels, and sometimes, how many times we encounter it.

This whole process starts with something called encoding - the way raw experiences are shaped into something the brain can actually store.

We can encode information visually (as a picture), acoustically (as a sound), or semantically (by tying it to meaning).

The more vivid, emotional, or multi-sensory the experience, the stronger the encoding tends to be.

Sometimes this happens automatically, like a smell pulling you straight back to a childhood kitchen.

Other times, it takes work: repeating someone’s name after you meet them, studying for an exam, rehearsing a new skill until it sticks.

Short-term memory, limited as it is, uses some clever tricks to make the most of its space.

One of those tricks is chunking - taking small pieces of information and grouping them together into bigger, more manageable bits.

Instead of trying to remember seven random numbers like 5-1-3-8-7-2-9 individually, your brain instinctively groups them into something like 513-8729, making it easier to hold onto.

But even with strategies like chunking, short-term memory can only stretch so far.

For something to become a lasting memory, the brain has to go deeper.

It needs to physically change.

That change happens through a process called long-term potentiation.

When neurons fire together often enough, the connections between them strengthen. Over time, the pathways become more efficient, and the memory becomes easier to retrieve.

This isn’t just metaphorical. It’s literal rewiring.

The brain builds new proteins. It reshapes synapses. It leaves behind a structural footprint of the experience. (SO cool!!)

Memories don’t "save" all at once either.

They start fragile and malleable, needing time to stabilize.

This is one of the reasons sleep is so important.

While we rest, the brain quietly revisits the day’s events, replaying them and strengthening the ones it deems worth keeping.

Early on, the hippocampus plays a starring role, helping to consolidate and organize memories.

But over time, those memories migrate outward, settling into the broader network of the neocortex - the part of the brain responsible for higher-level thinking, creativity, and making sense of the world.

So no, memories aren't neatly filed away like books in a library.

They’re living, breathing networks, constantly shifting and being shaped by attention, experience, emotion, and time.

Memory diagram

A Quick Note

The rest of this article is available exclusively for members of The Buffalo Herbalist Community.

We’ll be diving deeper into the brain’s architecture of memory - exploring the role of the hippocampus, the mechanisms behind short-term memory loss, how memories are physically stored and consolidated over time, the fascinating ways the brain keeps our experiences alive, and how Ginkgo biloba may help protect and support this living network.

If all of that sounds as interesting to you as it does to me, you can continue reading below.

I'm so glad you're here.