The Bitter Side of Herbal Medicine—And Why You Actually Need It

herbal medicine reminds us that not all healing is sweet—sometimes it's the bitter things that bring us back to balance.

One of the first things we learn in herbalism is how to slow down and pay attention to our senses. This practice is called organoleptics—a fancy word for tuning into how your body reacts to a plant through taste, smell, sight, touch, and even sound.

It’s the art of observation.

How does the herb smell when you first open the jar? What about after you’ve made an infusion or decoction? What color is the liquid? How does it taste? What does it feel like in your mouth—drying, moistening, warming, cooling?

This practice is one of my favorite ways to get to know a plant, especially when you’re first meeting it—and honestly, when it’s meeting you too.

I remember sitting around a big wooden table during a class at the Northern Appalachia School, where our teachers, Calyx and Jaybird, passed around jars of tinctures and infusions for us to sample.

We were told to hold it on our tongues and just observe. It was my first time doing anything like this, and it blew my mind how immediately my body responded.

Some tinctures made my mouth dry up on the spot—thanks, tannins. A marshmallow root infusion felt like it gently coated and soothed everything from my tongue to my stomach. And cayenne? Yeah… that one had me feeling like steam was coming out of my ears. That was definitely a moment.

But the one that really sticks out? Yellow dock. If you could see my face right now… just picture that emoji with the straight-line mouth. You know the one. If you’ve ever tasted Yellow Dock, you already know. It’s bitter. Like, deeply bitter. Possibly the bitter-est of them all.

We were told that most of us have forgotten what true bitters taste like—because let’s be real, it’s a flavor we’re taught to avoid. (I’ve also read that our bodies are hardwired to be suspicious of bitter tastes since a lot of poisons are bitter... which makes sense biologically.)

But here’s the thing: this taste, and the entire class of bitter herbs, is essential for our digestive system.

Bitters wake up digestion. They get things moving, help your body prepare for food, and can be incredibly helpful when things feel a little off in the belly.

Today, we’re going to explore just a few of my favorite herbs that fall into this category—bitter herbs and a couple that bridge the gut-brain connection.

There are so many amazing plants in this realm, so let this just be your starting point. As always, take what resonates, and do your own research to find what works best for your body.

Let’s get into it!

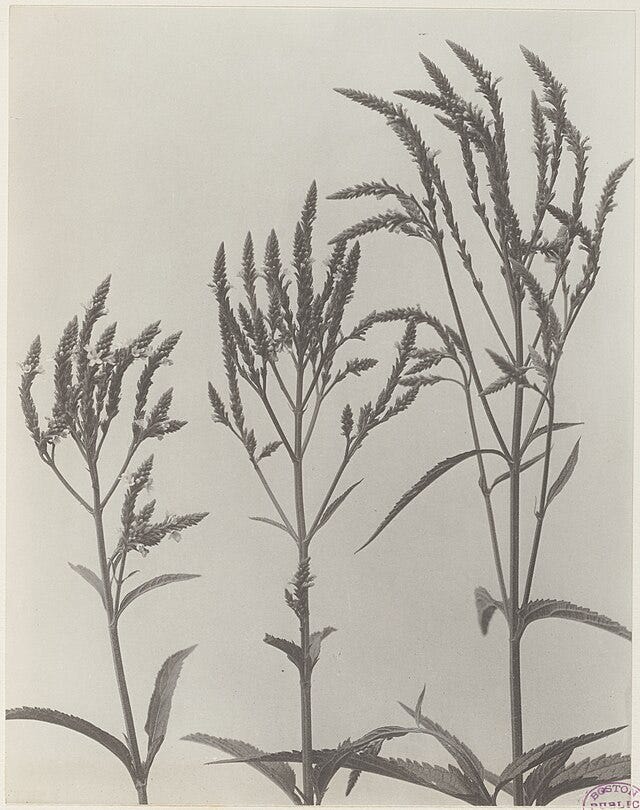

Blue Vervain; Lincoln, Edwin Hale

The Bitter Truth

Bitters play a huge role in digestion—and honestly, the rest of the body too. At their core, bitters are exactly what they sound like: herbs with a bitter taste. But don’t let that simplicity fool you. Their effects go way beyond flavor.

Bitters help tone and support the digestive system, but they also offer an opportunity to treat the whole body, which is why they’re such an important part of holistic and preventative herbal medicine.

These herbs can range from gently bitter (like dandelion leaf or yarrow) to the kind of bitter that makes you question your life choices—looking at you, wormwood, mugwort, and yes... yellow dock. 😐

Despite the strong flavor, bitters are absolutely worth exploring. They’re foundational in herbal practice for a reason.

Herbalist David Hoffman refers to the compounds responsible for that signature bitter flavor as bitter principles—and there’s a whole variety of them. These are the chemical constituents that light up the bitter receptors at the back of your tongue.

They can come from different molecular families like monoterpenes, iridoids, sesquiterpenes, and alkaloids—all of which are just science-speak for “this is what makes that tea taste the way it does.”

Now, let’s get a little nerdy for a second.

Taste is actually a form of chemoreception, which means our body is picking up chemical signals and translating them into sensations. We have around 9,000 taste buds—little chemoreceptors that help us make sense of flavor. In adults, they’re mostly hanging out along the edges of the tongue, but in kids, they’re spread out across the whole thing (which might explain why children can be so dramatic about bitter flavors—I must still be a child).

Different parts of the tongue are more sensitive to different tastes: sweet, salty, sour, and—you guessed it—bitter.

A Tiny Tongue Exercise for Herbal Nerds

Here’s a little exercise I’d love for you to try:

Next time you’re sipping your favorite herbal tea, take a moment to really sit with it. Hold a sip on your tongue and notice where you're feeling the flavor the most. Is it at the tip? Along the sides? The back?

Then try it again with a different blend. It’s fascinating how different herbs light up different zones, and it’s a great way to start understanding your body’s sensory relationship with plants.

Bitters in Action: What They Actually Do

When you taste something bitter, you're not just wrinkling your nose or making that classic "ugh" face—you’re actually kicking off a whole cascade of biological responses. The sensation travels along your nerves to the central nervous system, which then signals the gut. That message tells your body to release a digestive hormone called gastrin, and from there, things really get moving—literally and figuratively.

Here’s what bitters can do once that chain reaction begins:

Stimulate appetite – This is super helpful during recovery or in conditions where appetite is low (like depression). That said, it’s not always ideal—if you’re already ravenous, bitters might not be your best friend at the moment.

Encourage the release of digestive juices – Bitters tell your pancreas, duodenum, and liver to step up, which can improve digestion—especially when it’s sluggish, inefficient, or irritated by allergies or sensitivities.

Support the liver – They help with detox and get bile flowing, which is huge. A lot of chronic health issues stem from an overburdened liver, so bitters taken after meals can be a gentle way to support that system.

Help balance blood sugar – Bitters can influence the secretion of pancreatic hormones like insulin and glucagon. That’s powerful—but also a heads-up: if you’re diabetic or managing blood sugar, bitters should be used cautiously and always under guidance.

Stimulate gut repair – Yep, bitters can even encourage the gut to heal itself by triggering self-repair mechanisms in the lining of the digestive tract.

Beyond Digestion: Bitters for the Body & Mind

And here’s where it gets really interesting: the benefits of bitters aren’t limited to digestion. Because digestion is so foundational to overall health, supporting it can ripple outward to other systems.

Bitter herbs can help regulate the heart and circulation, and some—even classics like mugwort and gentian—have a gentle uplifting or focusing effect on the mind. Some herbalists even say they have a subtle tonic effect on consciousness itself.

But—and this is important—you have to actually taste them.

No capsules. No sweeteners to mask the flavor. That bitter signal only works when the receptors on your tongue are activated. So yes, it might be unpleasant at first—but that moment of "ugh!" is part of the medicine.

Gentian (Gentiana lutea)

Let’s start with the bitter of all bitters—Gentian. This beautiful, bright-yellow alpine plant has a long tradition of use in herbal medicine, especially for digestive issues. And when I say it’s bitter… I mean it. We’re not playing around here.

Gentian isn’t just a bitter digestive ally—it also has some history steeped in legend.

The plant’s name is believed to come from Gentius, a king of ancient Illyria -any other ACOTAR fans? - (modern-day western Balkans), who ruled in the 2nd century BCE. According to the story, King Gentius was the first to discover the medicinal value of the gentian root, especially during times of plague and digestive illness.

He supposedly used it to treat his people and stave off disease, which earned the plant royal status in the eyes of later herbalists. Whether or not the king actually discovered it, the name Gentiana stuck.

In traditional European herbal lore, gentian was often considered a protector of vitality and strength. It was sometimes planted near homes or carried in pouches to ward off illness—especially those that came with fever, weakness, or “damp” conditions (think digestive sluggishness and poor circulation).

Because of its golden-yellow flowers and deeply rooted strength, some associated gentian with solar energy—used to bring warmth and stimulation where there was cold, stuck, or stagnant energy. A perfect symbolic match for its warming digestive fire.

By Cptcv at CC BY-SA 3.0, found here

We use the dried root and rhizome, and like all true bitters, gentian works by stimulating the release of digestive juices—saliva, gastric secretions, and bile. This not only preps your body for food but helps move things along if digestion feels slow or heavy.

It can even speed up how quickly the stomach empties, which makes it useful in cases of bloating, flatulence, sluggish digestion, or just that “ugh, I ate too much” feeling.

Gentian’s key herbal actions include:

Bitter

Hepatic (supports the liver)

Cholagogue (promotes bile flow)

Antimicrobial

Anthelmintic (helps expel parasites)

Emmenagogue (stimulates menstrual flow)

Because of its strength, gentian is typically used in small doses—but the effects are mighty. It’s most often taken before meals to support digestion or when you're dealing with a lack of appetite.

Important note: Gentian may cause headaches in some people and is not recommended during pregnancy or for anyone with gastric or duodenal ulcers. As always, check with your healthcare provider before starting any new herbal supplements.

How to Use Gentian

Tincture:

1–2 mL, three times a day (1:5 in 40% alcohol), ideally 15 to 30 minutes before meals.

Decoction:

Since we’re working with a root, you’ll want to make a decoction (basically a longer boil to extract the medicine). Use:

½ teaspoon of shredded gentian root

1 cup of water

Bring to a boil and simmer for 5 minutes. Strain and sip 15 to 30 minutes before meals.

Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata)

If you’re a millennial like me, you might remember vervain from The Vampire Diaries. I totally thought it was a made-up magical plant (because of course it repelled vampires), so imagine my surprise when one of my herbal mentors started class one day with, “Today, we’ll be covering Blue Vervain.” My reaction? A very loud and confused, “Wait… that’s real??”

Turns out not only is vervain real—it’s a deeply revered plant with an impressively long herbal résumé.

We use the aerial parts of Blue Vervain, and it’s classified as a bitter, nervine, antispasmodic, tonic, mild sedative, febrifuge, diaphoretic, relaxing expectorant, moderate hypotensive, and lymphatic. (Deep breath. Did I miss anything? Because wow.)

Blue Vervain isn’t just medicinal—it’s deeply magical, too. This plant has a long-standing place in folklore, ritual, and myth across cultures.

In Ancient Rome, vervain (Verbena officinalis, a close cousin of Verbena hastata) was considered so sacred that priests used it to purify temples and altars—which is why the Latin word verbena came to mean "sacred plant" or "altar herb." Roman soldiers were even said to carry it into battle for protection and strength.

In Celtic tradition, vervain was one of the most revered magical herbs, believed to be a plant of prophecy, vision, and spiritual clarity. Druids used it in rituals to invoke divine insight, cleanse sacred spaces, and even as a charm to ward off evil. They often harvested it only at specific times—like at the rising of the Dog Star (Sirius) or during new moons—with elaborate rituals to honor its spirit.

Blue Vervain has also been known as “Herb of Grace”, “Holy Herb”, and “Enchanter’s Plant”, believed to offer both emotional healing and energetic protection. In folklore, it was used to calm heartbreak, soften grief, and open the heart to peace—echoing its modern-day use as a nervine that supports emotional and nervous tension.

Gut-Brain Support with a Side of Chill

So why is Blue Vervain so relevant to us now? Because it’s one of the best examples of an herb that works at the intersection of digestion and the nervous system—aka the gut-brain axis. Which we are pros at!

If you need a refresher, check these out: Your Gut & Brain Are Talking—Are You Listening? What Herbalists Need to Know & How Herbal Medicine Influences the Gut-Brain Axis: Pathways, Plants, and Practical Tips

Cody Hough, college student and photographer in the Michgian area.

This plant is especially helpful for people who carry their stress in their gut. You know the type (or maybe are the type): prone to overthinking, constant worry, a tight belly when emotions run high, and digestion that just can’t seem to settle down.

Blue Vervain is cooling and calming, especially when heat and tension are coming from the liver. This is often the case when strong emotions like anger, irritability, or internalized stress start to mess with digestion.

In Traditional Western Herbalism, we might describe this as “liver heat,” which can show up as restlessness, insomnia, tight shoulders, gut cramping, or a racing mind that won’t quit.

As a nervine, Blue Vervain works beautifully alongside other calming herbs. It helps ease tension, support an overworked nervous system, and is especially indicated when chronic stress leads to that classic mix of anxiety and low-grade depression—what the ancient Greeks called melancholy (literally: “black bile”). Emotionally, this plant is like a deep sigh for the body.

And because it’s also bitter, it brings with it all the digestive benefits we talked about earlier: encouraging bile flow, supporting liver function, and gently promoting movement through the digestive tract. When digestion is sluggish due to nervous tension (think stress-induced bloating or constipation), Blue Vervain can help get things moving again—without overstimulation.

How to Use Blue Vervain

Infusion:

You can prepare Blue Vervain as an infusion—just know that it will be bitter (and we want it to be!). That’s part of how it works. Sip ½ cup, 2–3 times a day to get the full effect.

Tincture:

Fresh plant extract (1:3 in 95% alcohol)

Dried plant extract (1:4 in 70% alcohol)

This one’s best taken in frequent, small doses throughout the day rather than all at once.

Important note: Blue Vervain is not safe during pregnancy, so please skip this one if you're expecting.

Wrapping Up

Bitters remind us that not everything healing has to be sweet. Sometimes, it’s the sharp, the pungent, the uncomfortable that wakes up our bodies—and our awareness. In a world that often tells us to smooth things over or numb them out, herbs like gentian and blue vervain invite us to feel, to notice, and to listen. They bring us back to ourselves, one slow sip at a time.

If this piece was helpful or sparked curiosity, I’d love it if you took a moment to like, comment, or re-stack—it truly helps this little herbal corner of the internet grow.

Later this week, we’re diving into one of the most-requested topics: parasites (yep, the gut theme continues!). We’ll start with GI parasites, what they are, signs to look for, and of course, the herbs traditionally used to support the body through them.

And if you’re a paid member of The Buffalo Herbalist Community, I’ve got a new perk just for you:

This Wednesday, I’ll be opening a paid-subscriber-only thread in the chat where you can ask me anything—herbal questions, personal curiosities, random plant thoughts. I’ll be answering a handful of those questions in this weekend’s upcoming podcast episode (fingers crossed for a Saturday release!).

If a paid subscription isn’t in the cards right now but you’d still like to support my work, you can always buy me a coffee here—and please know how deeply appreciated that is. 💛

Thanks for being here, for reading, and for letting herbs find their way into your daily rhythm.

Talk soon.

— Agy

Bibliography

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press.

Maier, K. (2021). Energetic Herbalism: A Guide to Sacred Plant Traditions Integrating Elements of Vitalism, Ayurveda, and Chinese Medicine. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Grieve, M. (1931). A Modern Herbal. Available online: http://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/g/genti105.html

Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal: A Complete Guide to Old World Medicinal Plants.

Cunningham, S. (1985). Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs.

Organoleptics - I've been experiencing full-body sensations on a deep level from the first moment I started tasting seeds, herbs, and plants. Didn't know there was a word for that! Gives me more angles to explain what I'm feeling when I'm in full-body flow, feeling everything all at once while being centered and present in the moment. Loved reading your writing, thanks for sharing!

I had to giggle at your pop culture references. I found myself having the same reactions when learning about herbs!