The Hidden Plastic in Tea Bags: A Guide for Herbalists and Tea Drinkers

the truth about microplastics, bioplastics, and how to make safer choices for your herbal infusions

I think one of the most beautiful things about modern herbalism is how accessible it’s become. These days, I can tell a curious friend or a client dipping their toes into herbal support to simply check their local grocery store’s tea aisle.

There’s something comforting about the low barrier to entry. Herbal teas are easy to find, affordable, and not the least bit intimidating. Most of us are already grabbing groceries anyway. Even if you don’t know your nervines from your nootropics, chances are you’ve had a brush with herbs in tea form.

Maybe you’ve sipped Sleepytime Tea, that iconic blend of chamomile and valerian whispering you toward rest.

Or reached for Throat Coat, with its slippery elm and licorice, and felt what real herbal demulcents can do for a sore throat.

Maybe you’ve tried a tulsi blend from Traditional Medicinals and felt a little more grounded on a day when you weren’t.

It’s all familiar. Gentle. Practical. It’s how many of us got started.

But here’s the thing: I don’t recommend boxed teas like I used to. At least, not without a disclaimer and a few caveats.

Because we need to talk about what else might be steeping in your cup.

Not just the herbs, but the bag itself.

We now have evidence that plastics, over time, are embedding themselves into the very layers of the earth, forming sediment strata like a new geological signature of human activity. That’s not abstract. That’s fossilization in real time. And if microplastics are cozying themselves into soil and stone, we’d be naïve to think they aren’t doing the same in us—in the gyri of our brains, the tissues of our gut, the blood that moves through us.

This article is about tea. But it’s also about paying attention.

What Are Microplastics, and Why Should We Care?

Plastic is everywhere. In our oceans, our food, the air we breathe, and increasingly, in us. Over 6 billion tons of plastic now circulate our world, and production isn’t slowing down. In fact, it's accelerating. By 2060, plastic waste is projected to triple, surpassing one billion tons annually. That’s more than just an environmental problem; it’s a biological one.

Plastics don’t quietly disappear. They break down into smaller and smaller pieces: microplastics (under 5 millimeters in diameter) and nanoplastics (under 1 micron). These fragments come from all directions: laundered synthetic fabrics, worn-down tires, food packaging, even cosmetics and toothpaste. They drift into the atmosphere and swirl in our water systems, eventually landing in our plates, cups, and lungs.

And yes, that includes your tea bag.

Recent estimates suggest that, depending on your age and sex, you might be consuming anywhere from 39,000 to 52,000 microplastic particles every year. And that’s just through food and drink—not accounting for what you breathe in.

Of the thousands of plastic compounds currently in use around the world, over 20 percent have been flagged by the European Union for their potential to persist in the environment, accumulate in human fat tissue, or cause direct toxic effects. Nearly 40 percent haven’t been studied enough to know one way or another.

In other words, we’re living with daily exposure to substances that are either known to be concerning or not yet fully understood.

Neuroscience News

Microplastics enter the body mainly through inhalation and ingestion. Maybe you’re drinking from a plastic water bottle. Maybe your takeout container leaches just a little something extra into your leftovers. Maybe your tea bag is sealed with plastic, steeping particles into hot water that carries them straight into your digestive tract. Maybe you’re using a plastic cutting board while chopping up your favorite veggies.

We now have direct evidence of these particles accumulating in human tissues. Microplastics have been found in the lungs, blood, placenta, breast milk, and even embedded within the carotid arteries of patients undergoing surgery for cardiovascular disease. In one study, the presence of microplastics in these arteries was strongly associated with a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death. Other findings suggest a link between microplastic load in the gut and inflammatory bowel disease, with higher levels correlating with more severe cases.

Here’s the catch: these studies are still observational. We don’t yet have clear causality. But we do have a mounting pattern. Plastics are turning up in the very places we never expected them to go.

And not just in us. They're in the Earth itself.

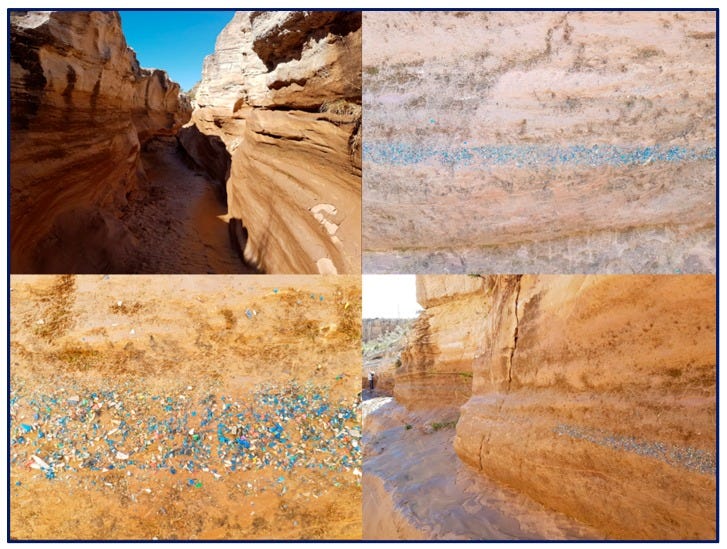

In recent years, geologists have started to recognize plastic as a stratigraphic marker of our time. These synthetic materials, now layered into riverbeds, roadsides, and canyons, are forming what some scientists call technofossils—artifacts of our plastic era preserved in sediment. In Spain and southern Italy, researchers have documented entire layers of earth infused with colorful fragments of synthetic polymer. Some of these deposits are even being used as construction material, replacing natural rock.

In effect, we’ve created a new geologic age. Many call it the Anthropocene, but others are now referring to it, with a kind of grim precision, as the Plasticene.

The visible layering and accumulation of plastic fragments embedded within the sedimentary walls of a Spanish canyon

Plasticene

The synthetic veils of microplastics carried on the wind, the gritty fragments woven into the ground—these are becoming as permanent as fossils.

And if they are embedding themselves into the very crust of the Earth, we would be foolish to think they aren’t doing the same within us.

In the grooves of our brains. The folds of our gut. The rhythm of our blood.

Toxicologists have a phrase that helps ground us here. As Paracelsus, the 16th-century physician often called the father of toxicology, once said, “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; the dose makes the poison.”

And that’s the trouble. We don’t yet know the dose. We don’t know the cumulative burden these particles leave behind. We only know that they’re present, and persistent.

What Microplastics Carry With Them

Microplastics aren’t just particles. They’re carriers. Once released into the environment or into our tea, they act as magnets for other pollutants. Some of those chemicals are part of their original makeup: plasticizers like BPA and phthalates, colorants, flame retardants, and stabilizers that were added during manufacturing. Others are picked up along the way: heavy metals like lead and cadmium, or environmental toxins from surrounding air, water, and soil.

Most of these substances aren’t chemically bound to the plastic itself. They can leach out, especially when heated, exposed to sunlight, or metabolized inside a living organism. Which means microplastics aren't just cluttering our insides. They may be delivering low-dose exposures of dozens of different chemicals, all with known or suspected toxicities.

The most pressing concern is endocrine disruption. Compounds like BPA and phthalates can mimic or block natural hormones, alter hormone metabolism, and interfere with the function of receptors. Even at very low levels, these disruptions have been linked to:

Fertility issues

Hormonal cancers

Thyroid dysfunction

Insulin resistance and obesity

Neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD and autism

Then there’s the matter of immune regulation and gut health. Some researchers suggest microplastics may contribute to chronic inflammation, disrupt the microbiome, or even act as vectors for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We already know they show up in gut tissue, and the correlation with diseases like inflammatory bowel disease is starting to raise red flags.

We come back to the principle from earlier: the dose makes the poison. But when exposure is ongoing, varied, and happening through everything from packaging to breath to tea, the cumulative burden becomes hard to quantify and impossible to ignore.

Why It Matters

I’m not here to fear-monger. I’m not saying you need to toss every tea bag in your cabinet or never enjoy a boxed blend again. What I am saying is this: if we’re going to work with plants for healing, we should also pay attention to the containers and processes surrounding them.

As herbalists, we need to know where our supplies come from. We can’t ignore what surrounds the herb, whether it’s plastic, chemicals, or contaminants from mass production. It’s not about perfection. It’s about awareness.

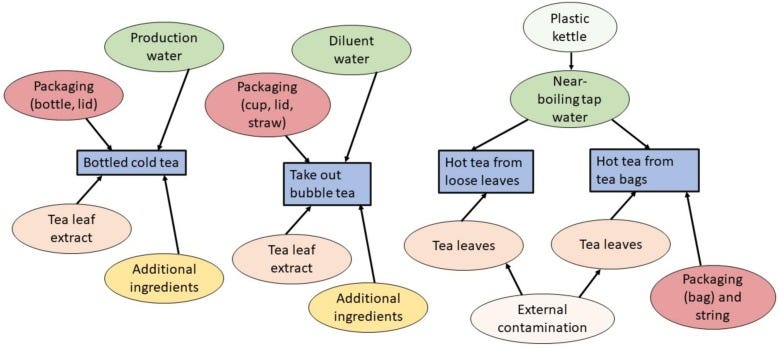

What the research shows is this: nearly all tea-based drinks, whether bottled, bagged, or steeped loose-leaf, carry some level of micro- and nanoplastic contamination. The sources are varied: packaging, water quality, tea leaves themselves, and even the manufacturing environment.

But the biggest contributor by far? The tea bag. Especially those made with plastic or marketed as "biodegradable." When exposed to hot water, mechanical stress, and steeping time, these bags and their strings shed significant amounts of particles into your cup.

In most cases, the plastics found in the tea match the materials used to make the bag, whether nylon, polypropylene, or plant-based polymers like PLA. Some studies even note contributions from external contamination likely introduced during processing or packaging.

One additional source that hasn’t been widely accounted for? Plastic kettles. Some studies suggest that steeping in water heated in plastic kettles could be introducing yet another layer of microplastic exposure, particularly in the smallest size ranges.

At the end of the day, if we’re using tea as a healing medium, we owe it to ourselves and the people we serve to understand the whole picture. That includes the invisible particles that come along for the ride.

Microplastics in Tea

So... Which Tea Bags Are Actually Plastic-Free?

I know. You’re probably scratching your head or giving the screen the side eye like, “Okay Agy, but what am I supposed to do about this? I’m not going to stop drinking tea!”

Don’t worry, I gotchu.

By now, it probably goes without saying that tea bags made without plastic are the better option. But with most traditional tea bags laced with microplastics or sealed with plastic adhesives, what actually counts as plastic-free? Thankfully, a few brands are starting to swap out synthetic polymers for more natural, compostable fibers.

Let’s break down a few of the materials you might come across if you’re trying to avoid plastic in your daily brew:

Abacá (Banana Fiber) Tea Bags

Abacá, a fiber from a species of banana plant, is a quiet hero in the plastic-free tea bag movement. It’s strong, heat-resistant, and completely free from synthetic fibers or plastic. A handful of reputable brands use it in combination with wood pulp or cellulose.

Organic Cotton Tea Bags

Some premium teas use unbleached organic cotton to create single-use sachets or reusable bags. These are a great choice if you want to avoid industrial materials altogether. You can even DIY your own with muslin or cotton pouches.

Wood Pulp & Hemp Tea Bags

A blend of wood pulp and hemp creates a sturdy, plant-based option that’s free of plastic while holding up well during steeping. These materials are renewable and less likely to leach microplastics.

There’s a helpful article by Green Choice Lifestyle (linked below) that covers this topic in depth. It features 32 tea brands currently offering what are labeled as “plastic-free” options, and I’ll link it below for those of you who want to dive in and do a little ingredient-sleuthing.

But before you click away, let’s pause for a quick reality check.

“Plastic-free” doesn’t always mean microplastic-free.

Many of these alternative tea bags are made from paper, bioplastics, or compostable materials like PLA. While they may not look or feel like plastic, they can still shed microplastic fragments, either during production or when steeped in boiling water. In this context, plastic-free usually means the bag isn’t made from obvious polymers like nylon or polypropylene, not that it’s entirely free from synthetic contamination.

So, what exactly is PLA?

Polylactic acid is a bioplastic made from fermented plant starch, usually derived from corn, sugarcane, or cassava. It’s often marketed as eco-friendly because it comes from renewable sources and, in theory, it’s biodegradable.

But here’s the kicker: PLA usually needs high-heat, industrial composting conditions to break down properly. And even then, it can behave like conventional plastic when exposed to hot water—like, say, your morning cup of tea.

Personally, I’ve opted out of the confusion altogether. These days, I stick with loose leaf tea in a French press, where I know exactly what’s going into my cup.

But if you’re a tea bag loyalist, I encourage you to explore your options and check out the Green Choice Lifestyle article. Just keep your eye on ingredient labels and remember that even “natural” materials aren’t always as innocent as they seem.

The truth is, we live in a plastic world—and we’re only just beginning to understand the toll it takes on our bodies, our ecosystems, and even the medicines we brew with care and intention. Microplastics may be invisible, but their presence is anything but benign.

This isn’t about guilt or fear. It’s about awareness.

About asking questions. About knowing where our herbs come from, how they’re prepared, and what carries them into our cups.

As herbalists, as tea drinkers, as humans living through the Plasticene, we deserve to know what we’re steeping ourselves in.

If this sparked something in you, share it with someone who still dunks their tea bag without thinking twice. And if you’re ready to go deeper into topics like this, from the plants we love to the systems they’re entangled in, consider subscribing to The Buffalo Herbalist.

Whether free or paid, your presence here matters. Let’s keep learning together.

-Agy | The Buffalo Herbalist

P.S. If this piece offered you something meaningful—whether insight, reflection, or a deeper sense of curiosity—please consider supporting my work by becoming a member of The Buffalo Herbalist Community. If a subscription isn’t possible right now, leaving a small tip is another thoughtful way to help keep this space thriving.

Your support, in any form, is deeply appreciated.

Bibliography

Nihart, A. J., Garcia, M. A., Hayek, E. E., Liu, R., Olewine, M., Kingston, J. D., Castillo, E. F., Gullapalli, R. R., Howard, T., Bleske, B., Scott, J., Gonzalez-Estrella, J., Gross, J. M., Spilde, M., Adolphi, N. L., Gallego, D. F., Jarrell, H. S., Dvorscak, G., Zuluaga-Ruiz, M. E., . . . Campen, M. J. (2025). Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1

Campanale, C., Massarelli, C., Savino, I., Locaputo, V., & Uricchio, V. F. (2020). A detailed review study on potential effects of microplastics and additives of Concern on human health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041212

Skinner, C. (2019, January 9). The Plastocene – Plastic in the sedimentary record. Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Palaeontology. https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/ssp/2019/01/09/the-plastocene-plastic-in-the-sedimentary-record/

Microplastics are everywhere — we need to understand how they affect human health. (2024). Nature Medicine, 30(4), 913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02968-x

Ali, T., Habib, A., Muskan, F., Mumtaz, S., & Shams, R. (2023). Health risks posed by microplastics in tea bags: microplastic pollution – a truly global problem. International Journal of Surgery, 109(3), 515–516. https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000000055

Fard, N. J. H., Jahedi, F., & Turner, A. (2024). Microplastics and nanoplastics in tea: Sources, characteristics and potential impacts. Food Chemistry, 466, 142111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142111

Antoniadou, K. (2025, May 28). 32 Plastic-Free Tea Bag Brands Without microplastics in 2025. Green Choice Lifestyle. https://greenchoicelifestyle.com/plastic-free-tea-bag-brands/

This is excellent!

I love how you cite your sources!