The Nervous System Explained: What Every Herbalist (and Curious Mind) Should Know

a beginner-friendly look at how stress, mood, and the nervous system connect—and how herbalists approach healing from the root

I’ll be honest…neuroanatomy was never my favorite subject. Not because it wasn’t fascinating, but because it felt like an endless map of grooves and folds and regions that all looked the same.

So much memorization, so many names that blurred together.

But here’s the thing: the nervous system is essential. Not just medically, but existentially. It’s the thread that ties every part of us together—mind and body, sensation and thought, memory and movement. It governs our perception of the world and, in many ways, our experience of being alive within it.

It’s through the nervous system that we connect with one another. With nature. With spirit.

Some call the brain the seat of consciousness—but perhaps it’s more like a meeting ground, where the physical and the unseen intersect. Where souls glance across the synapse and recognize one another—not just in humans, but in every living thing.

As I’ve mentioned before in this publication, my work is about making the body—and its brilliance—more accessible. Not by dumbing it down, but by translating it. Making it feel familiar, approachable.

So, here’s my invitation: let’s start small. The nervous system is vast, intricate, and layered. This isn’t a dive into the deep end—just a toe in the water. A place to begin.

Here is a quick link to an earlier article I wrote on how to support an overstimulated nervous system with herbs:

Nerves, Signals, and the Spark of Being

The nervous system is how your body listens, speaks, remembers, and reacts. It’s how we sense the world around us—and how we respond to it, consciously or not.

Whether you’re pulling your hand away from a hot stove, catching your breath after a surprise, or simply digesting lunch, your nervous system is involved. It’s not just about thinking and feeling—it’s also quietly managing your heartbeat, breath, digestion, and even how your body handles stress behind the scenes.

At the most basic level, this intricate system is made up of billions of nerve cells, or neurons. Just your brain alone houses around 100 billion of them.

Each neuron is like a living wire: it receives messages, processes them, and sends signals elsewhere—through tiny branches called dendrites and long tails called axons (some stretching over three feet in the body!). These signals allow you to feel pain, move a finger, or sense that something’s not quite right.

There are two main branches of the nervous system:

The central nervous system (CNS)—which includes your brain and spinal cord

The peripheral nervous system (PNS)—which includes all the other nerves that extend out into your body like a vast web

Together, they allow for both voluntary and involuntary functions.

Think of the voluntary side (the somatic nervous system) as the one you’re in charge of—walking, talking, smiling, lifting your arm. It’s the nervous system under your command.

Then there’s the autonomic nervous system, also called the involuntary system—and it runs the background processes you don’t have to think about: keeping your heart beating, your lungs breathing, and your gut moving.

This system is always on, adjusting and responding to what your body needs in real time. If you're too hot, it helps you sweat. If you're panicking, it might spike your heart rate and tighten your muscles before you even realize why.

The autonomic system has three key parts:

Sympathetic – your gas pedal; kicks in when you’re stressed, scared, or in danger (“fight or flight”)

Parasympathetic – your brakes; helps you rest, digest, heal, and return to baseline

Enteric – sometimes called your “second brain,” this system lives in your gut and manages digestion almost completely on its own

While these systems often act in opposition—one activating, the other calming—they also collaborate. You need them both. Together, they form a dynamic system of balance: speeding things up when it’s time to act, slowing things down when it’s time to recover.

And when that balance is off? That’s when we start to feel it—in our moods, our energy, our sleep, and even our digestion. In the next section, we’ll look at what it means when the nervous system is out of rhythm—and how that can manifest as anxiety, depression, or chronic overwhelm.

Mood, Anxiety, and the Brain: What’s Really Going On?

Depression and anxiety aren’t just “in your head”—they’re rooted in complex interactions between your brain chemistry, nervous system wiring, hormonal feedback loops, and even your genetic makeup. When people talk about mental health as a “chemical imbalance,” that’s only scratching the surface.

At the core of both mood and anxiety disorders are disruptions in the nervous system’s communication network.

Neurotransmitters (like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and GABA) are the messengers that help different parts of the brain talk to one another.

But in people experiencing depression or anxiety, those messages can get scrambled—either too loud, too soft, or misfiring altogether.

These shifts happen within areas of the brain deeply tied to emotion, memory, and decision-making. The limbic system, often called the emotional brain, includes structures like:

The amygdala, which scans for threats and governs fear responses

The hippocampus, which helps regulate memory and plays a key role in stress feedback loops

The prefrontal cortex, where we make decisions, regulate behavior, and interpret social and emotional cues

When these systems fall out of sync, it becomes harder to regulate mood, manage fear, or even access feelings of pleasure or motivation. The prefrontal cortex normally helps calm the emotional intensity of the amygdala—but under chronic stress or trauma, that balance can break down. Over time, the brain becomes wired for hyper-vigilance, emotional numbness, or low mood.

Neurotransmitters & Neuropeptides: The Chemical Messengers of Emotion

Let’s simplify this: your brain talks to itself using neurotransmitters—chemicals like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, and GABA. When these are out of balance, mood shifts follow.

Low serotonin is often linked with depression

Low GABA or excess glutamate can trigger anxiety and restlessness

Dopamine is tied to motivation and reward—too low, and we lose our spark

Norepinephrine helps with focus and alertness—but too much can feel like anxiety in overdrive

Alongside neurotransmitters, your brain also uses neuropeptides—larger signaling molecules that fine-tune emotional and physical responses. These include:

CRF (Corticotropin-Releasing Factor) – major stress signal, often elevated in chronic anxiety or PTSD

NPY (Neuropeptide Y) – helps regulate stress resilience; lower levels have been found in people with depression

Oxytocin & Vasopressin – connected to bonding, attachment, and social safety

Galanin & CCK – influence pain, digestion, and mood, often found altered in anxiety or depression states

These chemical messengers don’t work alone—they’re part of a vast network connecting the brain to the body.

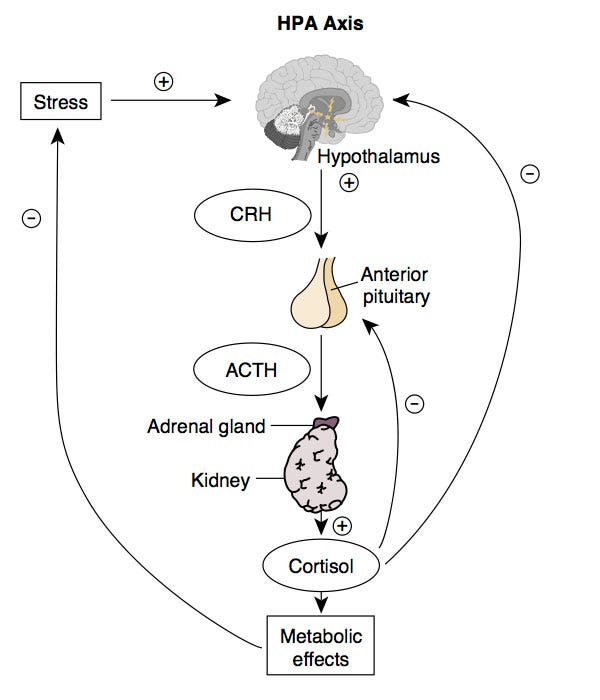

One key pathway in this network is the HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), the system that governs how we respond to stress. It’s a feedback loop between the brain and the adrenal glands that regulates cortisol, your main stress hormone.

In depression, the HPA axis often becomes hyperactive, flooding the body with stress hormones and exhausting the system. In PTSD, interestingly, it can become underactive, as if the system burned out from chronic overload..

HPA axis

The Autonomic Nervous System and Emotional Regulation: A Two-Way Street

When we talk about mood and mental health, it’s easy to picture the brain as the central hub. But your autonomic nervous system (ANS)—the part of your nervous system that controls involuntary functions like heart rate, breathing, and digestion—is just as deeply involved in how you feel, move, and respond to the world.

The ANS plays a central role in motivation, stress responses, and emotion regulation. It’s often divided into two branches:

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS)—your “fight or flight” mode

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)—your “rest and digest” mode

But here’s where it gets interesting:

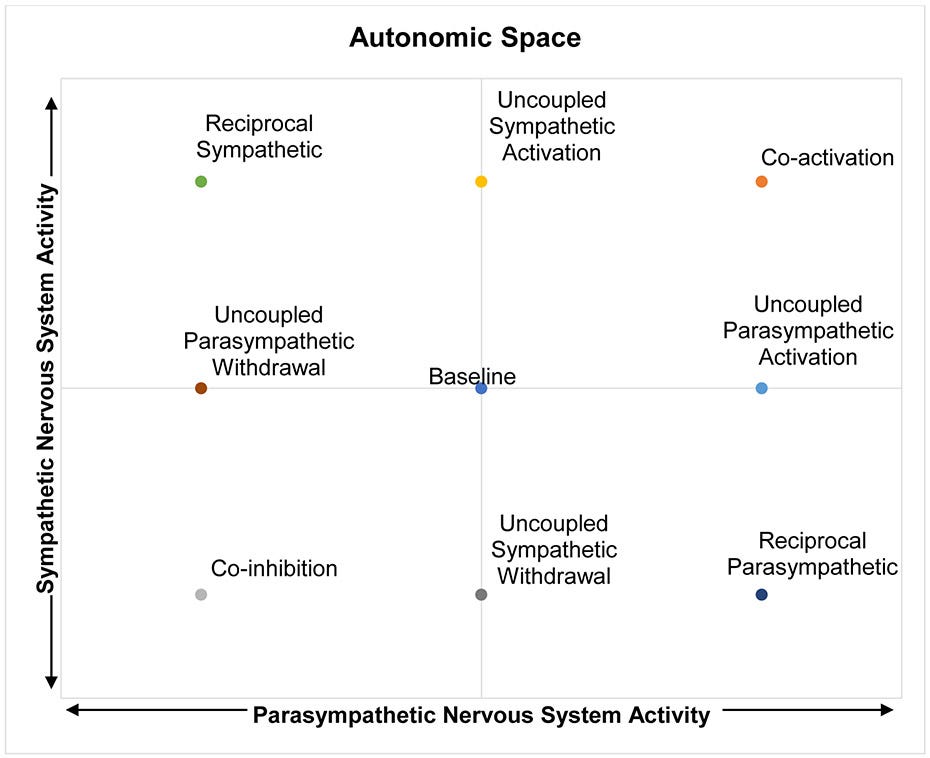

These systems don’t operate on a simple see-saw. They aren’t always in opposition. Sometimes they activate together, sometimes one steps back while the other ramps up, and sometimes they move independently—each responding to internal cues and external context.

This model—called autonomic space—helps us understand why some people freeze in fear while others lash out, or why one person recovers quickly from stress while another stays stuck. It's not about one branch "winning"—it's about how well the two can coordinate and respond flexibly. That flexibility is a sign of resilience.

Autonomic Space

Heart rate, for example, can increase not just because of sympathetic activation (the gas pedal), but also due to parasympathetic withdrawal (lifting the brake). When both branches are active or inactive at the same time, the effects can cancel out—or create strange, paradoxical feelings of tension and fatigue.

The vagus nerve, a major player in the parasympathetic system, plays a particularly important role in regulating mood and social engagement. High vagal tone (measured through something called RSA—respiratory sinus arrhythmia) is associated with greater emotional flexibility, stronger recovery from stress, and more grounded connection to others.

Polyvagal theory, popularized by Dr. Stephen Porges, suggests that vagal tone isn’t just about physical health—it’s about our ability to feel safe, seen, and socially connected.

Genes, Trauma & Environment: The Roots of Vulnerability

Genetics can shape your susceptibility to mood and anxiety disorders—but they’re not destiny.

Instead of thinking in terms of “inherited disorders,” it's more helpful to think about predispositions—genetic patterns that increase sensitivity to certain stressors or influence how your brain handles neurotransmitters or hormone regulation.

Epigenetics—the study of how genes get turned on or off—shows us that our environment, diet, stress levels, trauma, and even relationships can all influence which genes get expressed.

This is why two people with similar genetic backgrounds can respond so differently to the same life experiences.

Studies in children have even shown that different anxiety traits—like social inhibition, separation anxiety, or panic-proneness—can stem from unique combinations of genetic and environmental influences. It’s not one-size-fits-all. Your story matters.

The Takeaway

When the nervous system is stuck in a loop of overactivity—or collapses into under-functioning—it shows up as real, felt experiences: anxiety, depression, brain fog, fatigue, disconnection. But these aren’t failures of the mind. They’re messages from a body that has been adapting to stress for too long.

Understanding the interplay between the brain, neurotransmitters, hormones, and life experience can help us see these states more clearly—and treat them more gently.

Through an Herbalist’s Eyes: Listening to the Nervous System

As a clinical herbalist, I don’t just ask, ‘What’s the diagnosis?’ I ask, ‘What is your nervous system doing?’

Are you frozen or frazzled? Wired or wilted? Does your heart race before you speak up? Do you feel better after movement—or worse? What helps you drop into your body?

When we understand how the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work together—and how differently people experience stress—we start to see why herbs aren’t one-size-fits-all.

One person might need a cooling nervine like linden. Another might need grounding adaptogens. Another might need gut support to shift the enteric system out of a defensive pattern.

Understanding how autonomic activity shapes mood and emotion also helps us see why calming herbs don’t always feel calming for everyone. It depends on the pattern—is the system overfiring, under-responding, or stuck somewhere in between?

That’s the beauty of herbal medicine. It’s not about overriding your system—it’s about working with it. Supporting the shifts. Listening to the signals.

By Ivar Leidus - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

As you move through the rest of your week, I invite you to notice your nervous system—not as a machine to fix, but as a living part of you that listens, responds, and remembers.

Step outside, if you can. Let your bare feet touch the ground. Feel the wind on your skin. Notice how your breath changes when you hear birdsong, or how your shoulders soften in the presence of trees.

Ask yourself: What does safety feel like in my body? What does ease sound like in my breath?

You don’t need to analyze. Just observe. Let nature co-regulate you. Let your nervous system remember what it already knows: you’re part of the living world. You belong to it.

If this piece resonated with you, I’d love to hear from you. Feel free to like, comment, or restack to share it with someone who might need this reminder too. Your engagement helps this space grow—and keeps these conversations rooted in community.

In Tuesday’s post, we’ll slow down with one of my favorite herbal underdogs: Linden (Tilia spp.). It’s not the flashiest nervine, but it’s a deeply underrated ally when the nervous system needs softening, soothing, and space to breathe.

See you then,

-Agy | The Buffalo Herbalist

Bibliography

Weissman, D. G., & Mendes, W. B. (2021). Correlation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity during rest and acute stress tasks. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 162, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.01.015

Brigitta, B. (2002). Pathophysiology of depression and mechanisms of treatment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 4(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2002.4.1/bbondy

Martin, E. I., Ressler, K. J., Binder, E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2009). The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders: brain imaging, genetics, and Psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 549–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.05.004

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). (2023, May 4). In brief: How does the nervous system work? InformedHealth.org - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279390/

Thank you for explaining the connection between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. Very interesting, looking forward to learn more. Especially about how people respond differently, the connections to the nervous system, and how to recognize this.

Oof! I read this and I’m calmed. I have some observing to do….thank you. 🙏