Once you’re a little further into your herbalism journey, learning about Marshmallow is one of those fun, wait…what?! moments. You hear the name and immediately picture that perfectly toasted, golden-brown marshmallow—gooey and molten in the middle, nestled between a square of melting chocolate and a crisp, honey-sweet graham cracker. And then comes the real surprise: I can actually make marshmallows out of Marshmallow? Heck yeah! The original inspiration for that soft, pillowy confection came from this very plant. Consider that your newest herbal trivia gem.

But Marshmallow isn’t just about sweet nostalgia—it’s also a plant that teaches. It’s often the first introduction to mucilage (that delightfully slippery, soothing plant compound) and the magic of cold infusions. Instead of steeping in hot water, Marshmallow shines when allowed to infuse slowly in cool water, extracting its soothing, demulcent properties in a way that feels almost alchemical. It’s a gentle, yet powerful, lesson in both herbal actions and the many ways we can prepare and work with our plant allies.

A plant that inspired a beloved treat and a foundational herbal preparation? Now that’s one to remember.

Soft, Healing, and Steeped in History: Meet Marshmallow

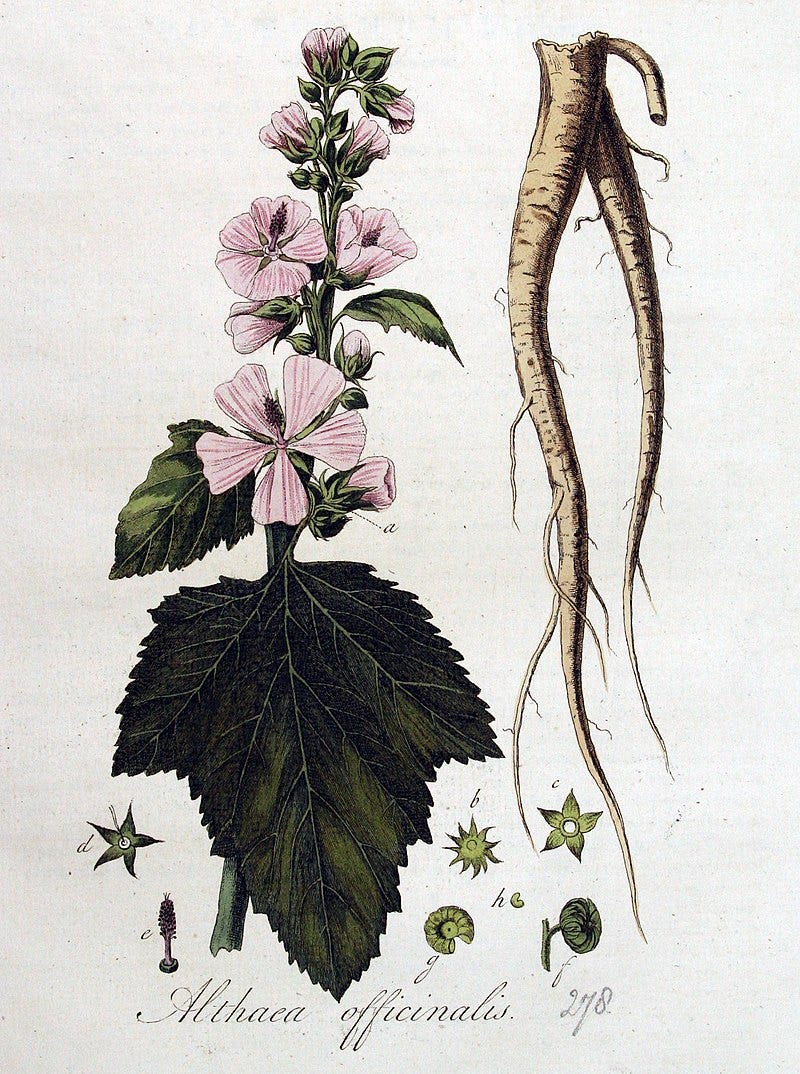

Marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) is a plant with a history as rich as its roots—literally. Native to the salt marshes of coastal Europe, it has since made itself at home in North America, thriving along inland waterways, ditches, and any place where moisture lingers. A true botanical globetrotter, this humble yet powerful herb has been cherished for centuries for both its medicinal and culinary uses.

What makes Marshmallow so special? Its roots and leaves are packed with mucilage along with pectins, sugars, flavonoids, tannins, salts, and phenolic acids. It’s a plant that doesn’t just comfort; it’s chemistry in action. And beyond its therapeutic properties, Marshmallow has been used as a nourishing food for over two thousand years. The Romans? They considered it a delicacy.

Even its name tells a story. The family name, Malvaceae, comes from the Latin mollis, meaning “soft”—an ode to its velvety leaves and soothing nature. Its genus, Althaea, traces back to the Greek altheo, meaning “to heal” or “to cure.” Fitting, isn’t it?

Marshmallow also has some well-known botanical relatives. The elegant hollyhock (Alcea rosea), the classic rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), and various hibiscus species all belong to the same family. These plants have even been used as substitutes for Marshmallow, since they’re often easier to find.

A Soothing Remedy, Rooted in Tradition

For centuries, Althaea officinalis has been a trusted ally in herbal medicine, especially in Europe, where it has long been used to ease coughs, sore throats, and inflamed mucous membranes. And modern research? It confirms what herbalists have known all along—Marshmallow isn’t just soothing; it’s scientifically backed. I’m so excited to show you the studies I’ve found!

At the heart of its medicinal power are water-soluble polysaccharides (5–11%), including galacturorhamnans, arabinans, glucans, and arabinogalactans. These compounds create a bioadhesive, mucin-like layer over irritated tissues, coating and protecting them from further inflammation. But Marshmallow’s magic doesn’t stop there. The root also contains flavone glycosides, phenolic acids, tannins, pectin, starch, and the coumarin compound scopoletin—all of which contribute to its anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective properties.

Clinical reviews have reinforced what herbalists have observed for generations—Marshmallow’s mucilage-rich extracts calm, coat, and protect delicate tissues, helping to ease irritation from the inside out. Whether it’s the throat, stomach, lungs, or urinary tract, this plant’s ability to relieve discomfort is more than just folklore.

What Exactly Is a Demulcent?

Before diving into the wonderful benefits of Marshmallow, let’s take a moment to define demulcents—because understanding how they work makes their effects that much more fascinating.

Demulcent herbs are rich in mucilage, a slippery, gel-like compound that soothes and protects irritated or inflamed tissues. When applied topically, demulcents are called emollients, but internally, they act like a protective barrier for delicate mucous membranes.

Now, here’s where things get interesting. Pharmacology doesn’t offer a fully satisfying explanation for how demulcents work throughout the body. We know that mucilage is made up of complex polysaccharides that become thick, slimy, and gummy when mixed with cold water. This physical property is easy to understand when we think about the digestive tract—demulcents coat the lining of the intestines, reducing irritation and soothing inflammation through direct contact.

But what about their effects beyond the digestive system? Some demulcents, including Marshmallow, seem to soothe the lungs, urinary tract, and even the bladder—places far removed from where they’re absorbed. How do they get there? That part remains a bit of a mystery.

What we do know is that all mucilage-rich demulcents share some key actions:

Soothe and protect the entire length of the digestive tract

Reduce sensitivity to gastric acids and bitter compounds

Help prevent diarrhea by stabilizing intestinal function

Relax digestive spasms that cause colic and cramping

Ease coughing by soothing bronchial tension

Relieve painful spasms in the bladder and urinary tract

As we’ll see with Marshmallow, this class of herbs offers far-reaching benefits—whether through direct contact or some yet-to-be-explained systemic effect.

Marshmallow: The Ultimate Soother

Marshmallow is the quintessential mucilaginous herb. Every part of the plant carries its signature demulcent properties, though the root is the real star. This soothing, mucilage-rich medicine coats and calms red, inflamed tissues from the mouth all the way down the digestive tract. While not curative, it’s a powerful ally for easing heartburn, gastric discomfort, and inflammation along the GI tract.

Remember how Marshmallow prefers salty marshes? Herbalists see this as an example of the Doctrine of Signatures—the idea that a plant’s appearance, growing conditions, or other natural traits hint at its medicinal uses. As herbalist Kat Mair explains, “The maxim that water follows salt is invaluable when you want to bring fluid to an area and loosen what has concretized.” Marshmallow, with its deeply hydrating, emollient properties, is the perfect herb for the job.

For example, in certain respiratory conditions, thick, hardened mucus can build up in the lungs, restricting oxygen exchange and leading to dyspnea (difficulty breathing). Marshmallow has long been used to help break up this tough, stuck mucus, making it easier to expel. The same principle applies to congested lymph nodes—when they become swollen, sluggish, or full of “sludge,” Marshmallow’s ability to soften and mobilize fluids makes it a key player in supporting the gut-lymph connection. Which we love.

But Marshmallow’s gifts don’t stop there. It’s also one of the most demulcent diuretics, making it a gentle yet effective addition to kidney and urinary tract blends. It soothes the pain of kidney stones, urinary tract infections, and other hot, irritating conditions. Looking for a powerful urinary support formula? Try this:

2 parts Uva ursi (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

1 part Corn Silk (Zea mays)

1 part Marshmallow root

One important note: skip the cranberry juice with this formula! Cranberry makes the urinary tract too acidic, interfering with the medicinal actions of these herbs.

Marshmallow Root & Mucosal Healing: The Science Backs It Up

For centuries, herbalists have turned to Marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) to soothe irritated mucous membranes, and now, modern research is confirming what tradition has long known. A recent study investigated how aqueous extracts of Marshmallow root and its mucilaginous polysaccharides interact with epithelial cells—the very cells that line the respiratory and digestive tracts.

How It Works

Marshmallow root contains rhamnogalacturonan-type polysaccharides, which form a bioadhesive, mucin-like layer over inflamed tissues. This protective barrier is well-documented, but researchers wanted to dig deeper: Does Marshmallow actively influence cellular behavior to support healing, or is it simply a passive coating?

To find out, Deters et al. (2009) tested aqueous Marshmallow extract (AE) and raw polysaccharides (RPS) on human epithelial cells (KB cells) and dermal fibroblasts (skin connective tissue cells). They analyzed:

Cell viability and proliferation – Does Marshmallow encourage cell growth?

Gene expression changes – Does it trigger a healing response?

Cellular absorption – Do these polysaccharides penetrate or just coat cells?

Key Findings

The study revealed that epithelial cells responded positively to Marshmallow extract. Even at low concentrations (1–10 μg/mL), both the aqueous extract (AE) and raw polysaccharides (RPS) significantly improved cell vitality. What’s interesting is that while the polysaccharides were absorbed by epithelial cells, they didn’t push them into excessive proliferation—suggesting a gentle, supportive effect rather than overstimulation.

The research also confirmed what herbalists have long observed—Marshmallow’s bioadhesive properties. The polysaccharides formed a protective, mucin-like layer over dermal fibroblasts, reinforcing their role in shielding and soothing irritated tissues.

Digging deeper, gene expression analysis showed an upregulation of proteins involved in cell adhesion, growth regulation, extracellular matrix formation, cytokine release, and apoptosis. In plain terms? Marshmallow isn’t just coating and calming—it may actually play an active role in tissue repair.

Interestingly, the study found no effect on fibroblasts. While Marshmallow clearly supports mucosal tissue, it didn’t stimulate fibroblast activity, reinforcing that its effects are specific to epithelial cells—the ones that line and protect our airways, gut, and urinary tract.

A plant that not only soothes but potentially signals repair? Modern science is just catching up to what herbalists have known all along.

What This Means for Herbal Medicine

This study validates Marshmallow’s traditional use for sore throats, digestive irritation, and respiratory inflammation. Not only does it create a soothing barrier, but its polysaccharides actively support epithelial cell function, promoting better mucosal healing.

Once again, science confirms what herbalists have known for centuries—Marshmallow isn’t just a passive soother; it plays an active role in supporting tissue repair and protecting irritated mucous membranes.

Marshmallow for Atopic Dermatitis: A Gentle and Effective Alternative?

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing skin condition that primarily affects infants and young children. While conventional treatments—like corticosteroids—are effective, they come with potential side effects, leading researchers to explore safer alternatives.

The Study Design

(Naseri et al., 2020) conducted a small clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of Marshmallow 1% ointment against Hydrocortisone 1% ointment in children with atopic dermatitis. The study included children aged 3 months to 12 years, who were randomly assigned to either:

The intervention group using Althaea officinalis 1% ointment

The control group using Hydrocortisone 1% ointment

Both groups applied their assigned treatment twice daily for one week, followed by three times per week for the next three weeks. The severity of AD was measured using the SCORAD score, a standard tool for assessing disease progression.

Key Findings

Both groups saw a significant decrease in SCORAD scores, indicating improvement.

However, by the end of the study, the Marshmallow group showed a greater reduction in disease severity compared to Hydrocortisone.

This difference was statistically significant when compared to both baseline (p = .015) and week 1 (p = .018), suggesting Marshmallow’s therapeutic effects may be comparable—or even superior—to Hydrocortisone for mild-to-moderate AD.

The Science Behind the Soothing Effect

Beyond the clinical trial, researchers conducted computational docking analysis to identify which phytochemicals in Marshmallow might be responsible for its anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects. They screened 33 phytocompounds against inflammatory targets, including TNF-alpha, IL-6, and phosphodiesterase (PDE) isoenzymes, all of which play key roles in the inflammatory response of atopic dermatitis.

Glycosylated compounds—phytochemicals with attached sugar molecules—showed the strongest affinity for these inflammatory enzymes.

The researchers suggest that this may be due to hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups of these compounds and the target enzymes, enhancing their inhibitory effects.

What This Means for Herbal Medicine

This pilot study suggests that Marshmallow 1% ointment may be an effective, natural alternative for managing atopic dermatitis in children—potentially outperforming low-dose Hydrocortisone. While further research is needed to confirm these findings, the results highlight Marshmallow’s potential as a gentle, anti-inflammatory skincare remedy.

With both traditional use and modern science pointing in the same direction, Marshmallow may soon become a go-to option for parents and practitioners seeking a soothing, plant-based approach to managing eczema and other inflammatory skin conditions.

Marshmallow for Dry Cough: Fast-Acting and Well-Tolerated

Marshmallow has long been used in herbal medicine for soothing dry coughs and throat irritation. While its traditional use is well established, a recent consumer survey set out to document real-world experiences with Marshmallow root lozenges and syrup—gauging their effectiveness, tolerability, and user satisfaction.

The Study Design

(Fink et al., 2018) conducted two independent, non-interventional surveys, recruiting 822 participants who purchased either Marshmallow lozenges or syrup (aqueous extract STW42) from pharmacies to treat dry cough and throat irritation. Each participant completed a 7-day questionnaire, tracking symptom progression and overall treatment experience.

Key Findings

Rapid relief – The majority of participants reported feeling relief within 10 minutes of taking Marshmallow syrup or lozenges.

High effectiveness – Both preparations were rated as effective for reducing oral and pharyngeal irritation and associated dry cough.

Excellent tolerability – Only three minor adverse events were reported for the syrup, and none for the lozenges.

Strong user satisfaction – Participants were generally satisfied with the treatment, reinforcing its value as a go-to herbal remedy for dry cough.

What This Means for Herbal Medicine

This consumer-based study confirms that Marshmallow root extracts provide fast and effective relief for dry cough while being exceptionally well tolerated. With its long history in herbal medicine and now strong user-reported evidence, Marshmallow remains a reliable choice for soothing throat irritation and calming persistent coughs—without the concerns of pharmaceutical side effects.

How to Prepare Marshmallow: The Cold Infusion Secret

Marshmallow is best known for its mucilaginous properties, and how you prepare it determines what compounds you’re extracting. Cold infusions are the gold standard for pulling out the soothing, slippery polysaccharides that make Marshmallow such a powerful demulcent.

Cold Infusion: The Best Way to Extract Mucilage

A cold infusion primarily extracts the mucilaginous polysaccharides, which coat and soothe irritated tissues. If you simmer the root, you’ll also extract starches—which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but a cold infusion gives you a purer mucilage extract.

How to Make a Cold Infusion:

Add 4 tablespoons of dried Marshmallow root to 1 quart of cold water

Let it sit for at least 4 hours, or overnight

Store it in the fridge while steeping for maximum extraction

Strain and drink as needed

Hot Infusion: Best for Leaves and Flowers

Marshmallow leaves and flowers can be prepared as a hot infusion, but there’s a catch—don’t boil them. High heat can destroy the beneficial polysaccharides, so steeping in warm, not boiling, water is the way to go.

Tincture: For Hardened Lymph Nodes

While mucilage does not extract well in alcohol, Marshmallow tincture still has its uses—particularly for softening hardened lymph nodes.

Dried root (1:5 ratio, 40% alcohol)

Dose: 10–60 drops, 1–4 times daily

If you’re looking for mucilage-rich benefits, stick with the cold infusion. But if your goal is lymphatic support, a tincture is a great addition to your herbal toolkit.

If you found this article helpful, go ahead and like, comment, and restack—it helps get this knowledge into the hands of more herbal-curious folks.

And, of course, I’d love to hear from you! Have you worked with Marshmallow before? Do you have a favorite way to prepare it? Drop your thoughts in the comments—let’s chat about this soothing, slippery wonder of a plant.

Now, onto what’s ahead! Later this week, we’ll be unraveling the mysteries of the Gut-Brain Axis, exploring how the gut and nervous system are deeply intertwined (and how herbs can support that connection).

Next Tuesday (April 1st), we’re diving into a much-requested topic—herbal support for parasites (yes, we’re going there).

Then, for The Buffalo Herbalist Community, Friday’s post will continue our deep dive into gut health with a look at the Gut-Liver Axis and the role of pre- and probiotic herbs in keeping our microbiome happy. :)

Curious about any of these topics? Drop your questions in the chat! Whether it’s parasites, the gut-brain connection, liver support, or probiotic herbs, let me know what’s on your mind—I’ll do my best to answer in the upcoming posts.

If you’ve asked me a question in the chat and haven’t seen it answered in a post, I’d love for you to drop it again in the comments of the related post! That way, I’ll be sure to see it and can respond where it fits best. Thanks for your patience!

Until next time, happy steeping, sipping, and studying!

-Agy

Bibliography

Deters, A., Zippel, J., Hellenbrand, N., Pappai, D., Possemeyer, C., & Hensel, A. (2009). Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from Marshmallow roots (Althaea officinalis L.): Cellular internalization and stimulation of cell physiology of human epithelial cells in vitro. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 127(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.050

Naseri, V., Chavoshzadeh, Z., Mizani, A., Daneshfard, B., Ghaffari, F., Abbas‐Mohammadi, M., Gachkar, L., Kamalinejad, M., Hajati, R. J., Bahaeddin, Z., Faghihzadeh, S., & Naseri, M. (2020). Effect of topical Marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) on atopic dermatitis in children: A pilot double‐blind, active‐controlled clinical trial of an in‐silico‐analyzed phytomedicine. Phytotherapy Research, 35(3), 1389–1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6899

Fink, C., Schmidt, M., & Kraft, K. (2018). Marshmallow root extract for the treatment of irritative cough: Two surveys on users’ view on effectiveness and tolerability. Complementary Medicine Research, 25(5), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489560

Easley, T., & Horne, S. (2016). The modern herbal dispensatory: A medicine-making guide. North Atlantic Books.

Hoffmann, D. (1988). The herbal handbook: A user’s guide to medical herbalism. Inner Traditions.

Maier, K. (2021). Energetic herbalism: A guide to sacred plant traditions integrating elements of vitalism, Ayurveda, and Chinese medicine. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise herbal, volume I: A complete guide to Old World medicinal plants. North Atlantic Books.

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism: The science and practice of herbal medicine. Healing Arts Press.

Marshmallow was paired with licorice root did wonders for gastritis!! I suffer from dry mouth also and this is sooo soothing. Thank you so much for the article!

It helped a lot when my Morbus Crohn was active.